Did you know that the use of DDT has lead to the eradication of malaria and significant reduction of typhus in Europe, North-America and many other parts of the world? Well, I didn’t.

So just a bit of history:

DDT was first synthesised in 1874. DDT’s insecticidal properties were discovered in 1939 by the Swiss scientist Paul Hermann Müller, who was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his efforts.

During World War II, DDT proved its remarkable effectiveness against typhus and malaria. It was discovered that in areas where malaria was endemic, the spread of the disease by mosquitoes could be prevented simply by spraying DDT twice a year on the inside walls of houses.

However, its shift in use as an agricultural insecticide eventually lead to an ecological disaster resulting in a ban for agricultural use on DDT in the 70’s and 80’s in most countries. Some countries even went to a total ban. This total ban in turn had a huge impact on the number of deaths from malaria, causing it to reconsider:

“Deaths from malaria have continued to rise since the 1970s, however, and countries affected by the disease and members of the scientific community have demanded that DDT should be used again for inside residual spraying. Additionally, extensive research and testing, published in the latest report of the UN joint meeting on pesticide residue in 2000, have shown that well managed programmes of spraying DDT indoors pose no harm to humans or to wildlife.”

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1570869/

Today, the World Health Organization promotes the use of DDT for public health purposes in malaria-prone countries, due to the lack of affordable and effective alternatives.

So DDT – once a great technology that has saved millions of lives – was/is left with only negative perception. But after the hysteria of banning DDT completely, reason has come back and restricted use is allowed where alternatives fail.

It seems to be an ever-recurring pattern that we are also going through today when it comes to plastics. Plastics came in and turned out to be the solution for many challenges like weight reduction, mouldability of complex shapes, cost reduction, chemical and corrosion resistance, durability and many other advantages. Plastics has contributed significantly to the society we live in today.

With the plastic soup and microplastics, there is a hysterical reflex of aiming for significant reduction and even banning its uses. However also in this case it is important to reflect on:

- what lies at the origin of the problems (Is it the technology itself? where it is used? the way it is used? How it is disposed?)

- the advantages the usage brings as compared to the negative effects that come with it

- the viability of alternatives and impact of potentially reduced performance (life cycle analysis)

Some learnings we can draw from this:

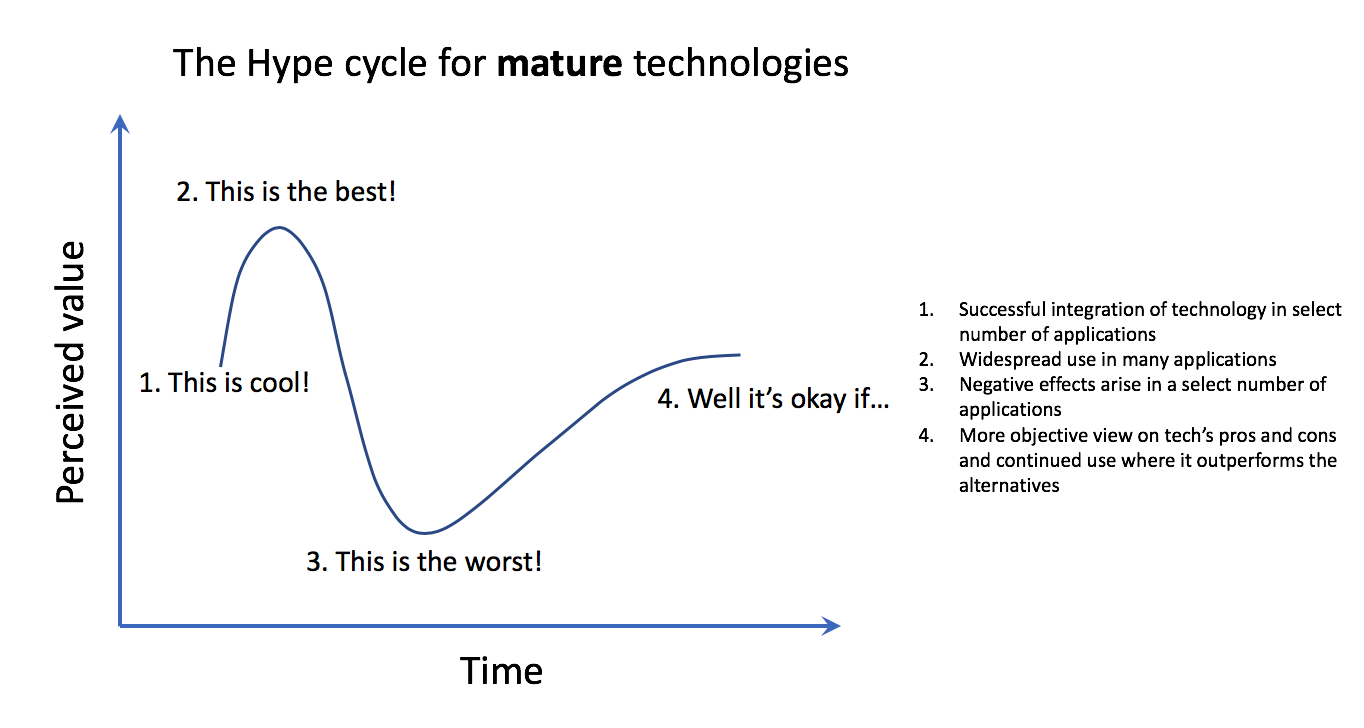

- Over a long timespan, materials (nanoparticles, plastics, PFOA,…) seem to be following a ‘Hype cycle’-like trend of perceived value over time on the market

- As specific negative effects of materials get discovered over time, society tends to forget the positive effects the material has brought (and is still bringing), and tends to focus excessively on the negative

- Detrimental effects within a certain application, should not necessarily result in a complete ban in all applications

In short, I would like to defend an approach where objectivism and balancing pros and cons rules over emotionalism. And obviously we should never settle for status quo and continue exploring for better alternatives or solutions!